It’s hard to think of another band that shaped American rock music and culture as quickly and fundamentally as Nirvana did. Coming out of the 80s, when you thought about rock music of the time, you conjured up images of tight pleather pants, rhinestone-embossed costumes, and of course, big, BIG hair. This was the age of so-called “hair metal”, filled with theatrics and hooks that could have topped the pop charts.

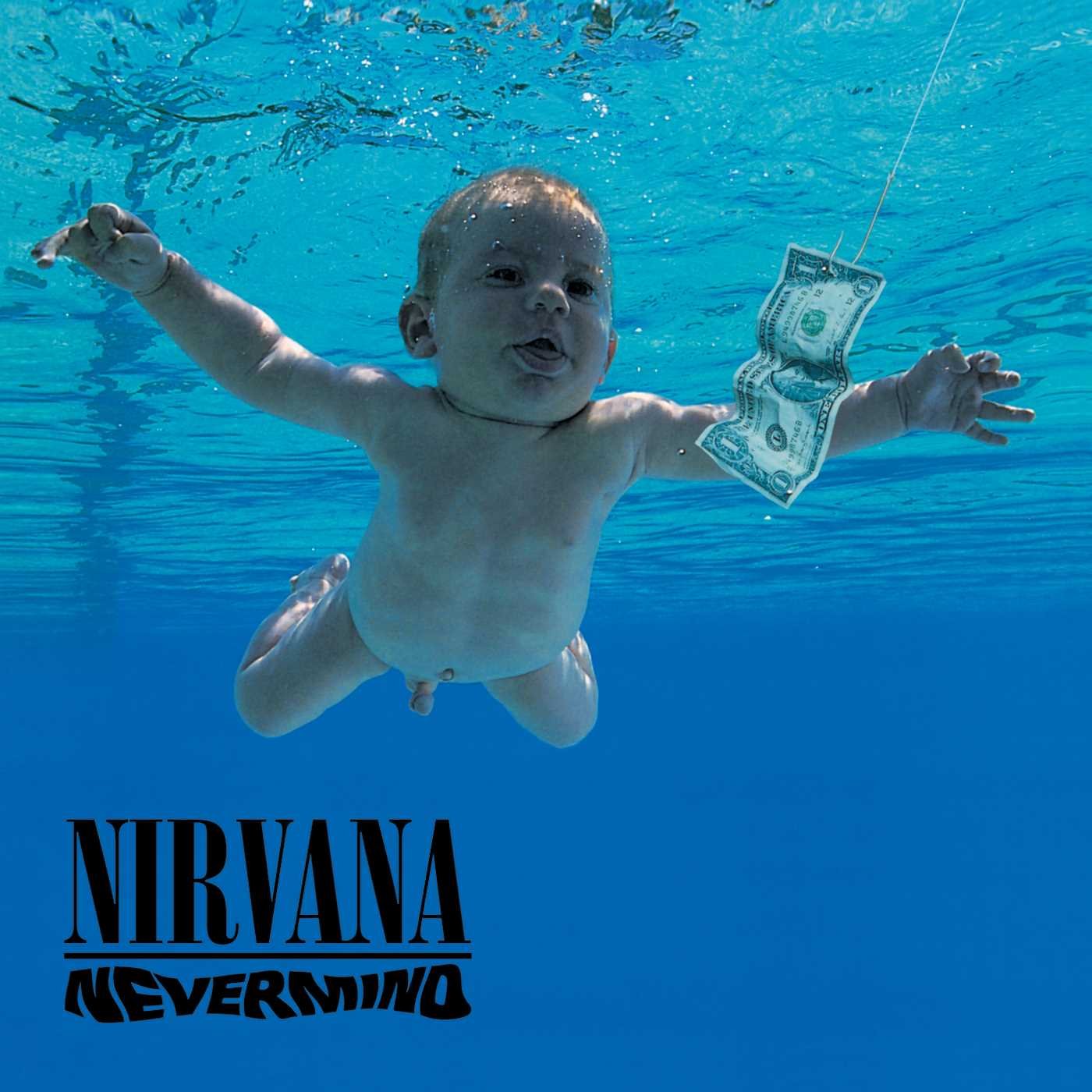

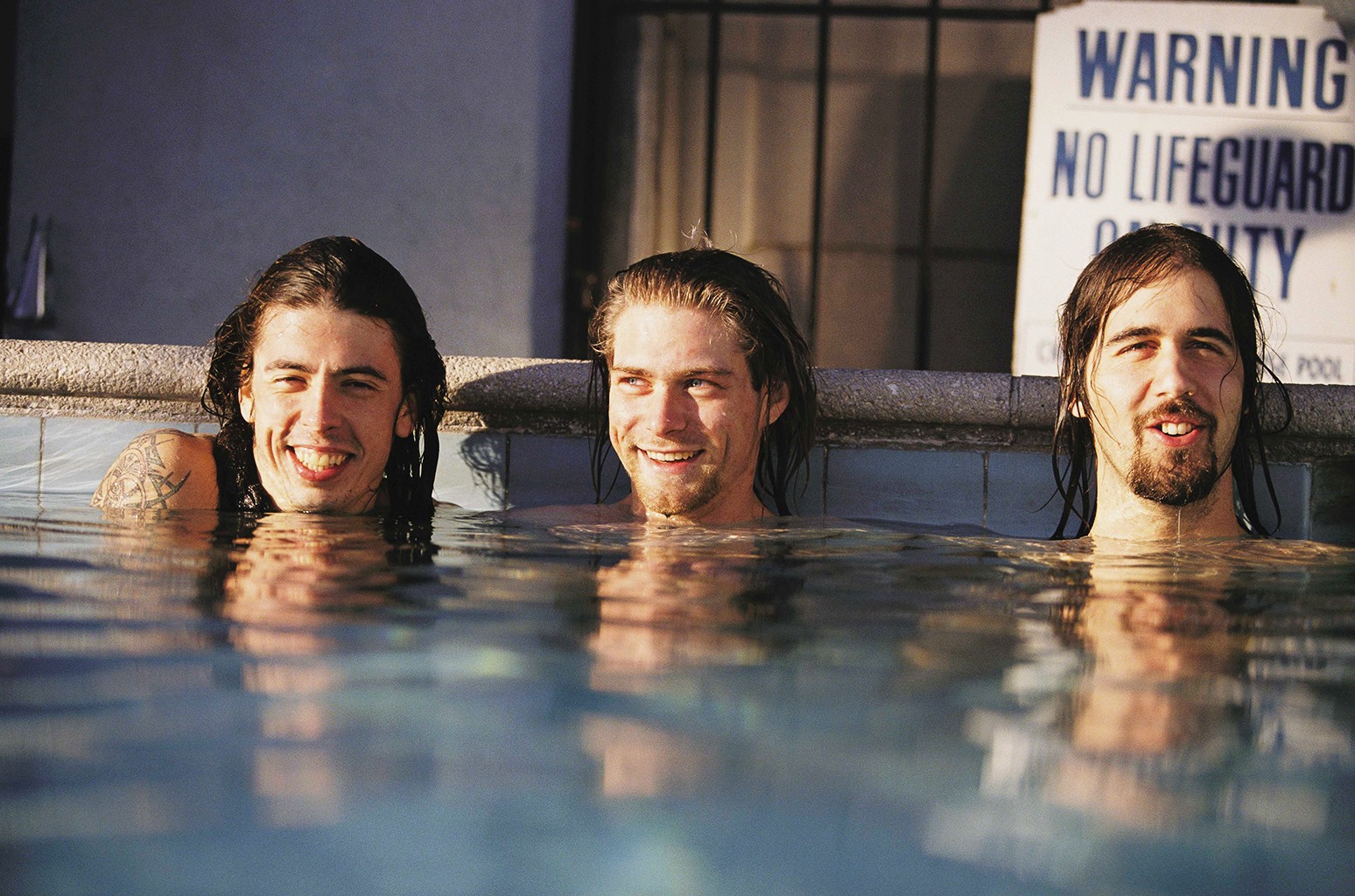

But then in come these kids from Aberdeen, Washington, who spent their high school years hanging around the practice spaces of the rock underground, immersing themselves in the pulsing heart of punk culture. By the time Nirvana released its first record Bleach, they had figured out how to tap into the growing frustration of the newest generation of teenagers, who were sick of the watered-down corporate drivel mainstream rock had become. But what really solidified Nirvana’s legacy was their sophomore album Nevermind, released 30 years ago.

Pop songstress Lorde told NME, “Nirvana are still as cool to my 19-year-old brother in 2021 as they were to 19-year-olds in 1991. That’s crazy to me – the fact that as a teenager I could see that that was so cool. It was undeniable and it’s still happening. That’s some powerful magic.”

Nevermind speaks the language of adolescence. The ear-worm melodicism drew teens in, and its punk rock ethos tapped into their growing frustration with authority. Throughout the album, Kurt Cobain’s lyrics can be difficult to interpret if you’re going through them with a fine-tooth comb, as many rock critics and parents alike did. “Come doused in mud, soaked in bleach, as I want you to be” growls Cobain on “Come As You Are”. That juxtaposition of sterilized filth, carnage, and desire speaks to something primal in every young person who hears it, something that’s beyond explanation or analysis.

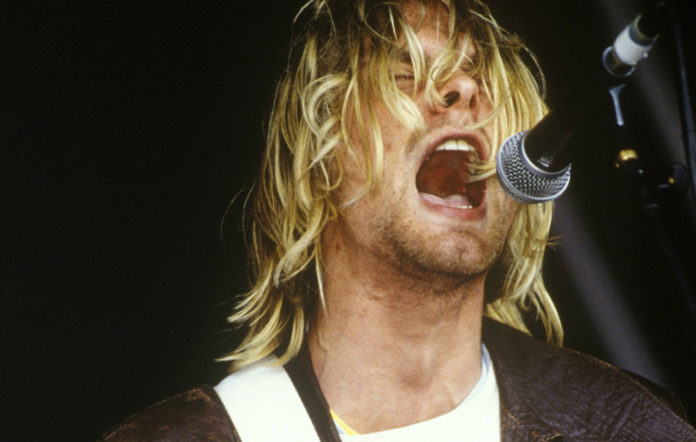

Lana Del Rey has said, “When I was 11, I saw Kurt Cobain singing on MTV and it really stopped me dead in my tracks. I thought he was the most beautiful person I had ever seen. Even at a young age, I really related to his sadness… [his music has] continued to be my primary inspiration – in terms of not wanting to compromise lyrically or sonically.”

Kurt knew the power of tapping into a visceral style of communicating with listeners. Perhaps this is best illustrated on “In Bloom” where he yells,

He’s the one

Who likes all our pretty songs

And he likes to sing along

And he likes to shoot his gun

But he knows not what it means

Knows not what it means

It’s as if Cobain saw the future, knew these songs wouldn’t be isolated to the punk kids, the losers, the ones who can speak his language. Everyone loves Nirvana, but that means every kind of person loves Nirvana. The undeniably gripping melodies on Nevermind put the record on the shelves of everyone from goths to jocks eventually, but Kurt Cobain reminds us that not everyone can decipher the true sentiments in his swirling lyrics and raucous riffs. Nirvana made sure we knew they were for the freaks first and foremost, and as a kid who felt lost amongst my peers like kids so often do, it felt like I was coming home.

I am firmly a Gen Z-er, born in 2001. I still remember the first time I heard Nirvana’s music. I was in middle school and probably had too much access to the Internet. In 2014 I would come home each day to spend hours surfing aesthetic “grunge” blogs on Tumblr. I remember seeing endless re-blogs of melting smiley faces with the iconic Nirvana emblem stamped below, images of Kurt Cobain looking contemplative as he hunched over a notebook, with ragged clothes and shaggy hair, sometimes with quotes that spoke to my all-consuming pre-teen angst. A quick google search led me to the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” music video, where I was suddenly transfixed by Cobain, the way he thrashed around on stage, the energy as he belted, hair smattered across his face so you could only catch glimpses of his eyes, the plain clothes he wore that reminded me of the kids who whipped by me on skateboards as I walked home from school. The song captured the frustration I felt at that age, having to constantly appease the adults in my life, who determined everything I did. But I, like many other 13-year-olds, was beginning to care less about what adults thought or wanted from me. I wanted to be cool like the high school kids I saw hanging around my small town skate park or movie theater, listening to rock music, wearing the coolest clothes, maybe even smoking cigarettes. Listening to Nirvana, I could imagine myself as one of those cool teenagers at a Nirvana concert, thrashing and screaming alongside kids who felt the same unyielding angst as I did. I was a good kid, with good grades, good manners, and a good family. But when I put my headphones on, I could feel the spirit of Kurt Cobain echoing how I really felt: that everything was bullshit. I didn’t know exactly what he was saying in the song, but I didn’t have to. I could feel it.

There’s a level of frustration and angst inherent in our teenage years, and it’s why we both love and hate teenagers. Young people challenge us because they haven’t been fully indoctrinated by the world yet. They can look at the world as it is, without the responsibility or get-by attitude of adulthood. Perhaps Nevermind resonates now more than ever before amidst the growing chaos of our political system, climate change, and ongoing health crisis. Whereas we may feel defeated by these insurmountable obstacles, the living breathing legacy of this album reminds us of when we were the kids who questioned the rules we were forced to follow, who resented the powers that be, and who found a community of people who felt just like we did through the music. The real triumph of Nevermind is that it forever captures a cultural transformation, one that strove to find a community of misfits who weren’t afraid to spit “fuck you” in the face of authority, and who couldn’t control frustration in the face of absurd systems. Though I’ve returned to this album 30 years after its release, it still feels timeless, if not more relevant than ever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.